Philosophy

易經

I Ching

Introduction – Chapter III

THE APPENDIXES

Subjects of the chapter

1. Two things have to be considered in this chapter:—the authorship of the Appendixes, and their contents. The Text is ascribed, without dissentient voice, to king Wăn, the founder of the Kâu dynasty, and his son Tan, better known as the duke of Kâu; and I have, in the preceding chapters, given reasons for accepting that view. As regards the portion ascribed to king Wăn, the evidence of the third of the Appendixes and the statement of Sze-mâ Khien are as positive as could be desired; and as regards that ascribed to his son, there is no ground for calling in question the received tradition. The Appendixes have all been ascribed to Confucius, though not with entirely the same unanimity. Perhaps I have rather intimated my own opinion that this view cannot be sustained. I have pointed out that, even if it be true, between six and seven centuries elapsed after the Text of the classic appeared before the Appendixes were written; and I have said that, considering this fact, I cannot regard its two parts as a homogeneous whole, or as constituting one book in the ordinary acceptation of that name. Before entering on the question of the authorship, a very brief statement of the nature and number of the Appendixes will be advantageous. (p. 27)

Number and Nature of the Appendixes

2. They are reckoned to be ten, and called the Shih Yî or 'Ten Wings.' They are in reality not so many; but the Text is divided into two sections, called the Upper and Lower, or, as we should say, the first and second, and then the commentary on each section is made to form a separate Appendix. I have found it more convenient in the translation which follows to adopt a somewhat different arrangement.

My first Appendix, in two sections, embraces the first and second 'wings,' consisting of remarks on the paragraphs by king Wăn in the two parts of the Text.

My second Appendix, in two sections, embraces the third and fourth 'wings,' consisting of remarks on the symbolism of the duke of Kâu in his explanation of the individual lines of the hexagrams.

My third Appendix, in two sections, embraces the fifth and sixth 'wings,' which bear the name in Chinese of 'Appended Sentences,' and constitute what is called by many 'the Great Treatise.' Each wing has been divided into twelve chapters of very different length, and I have followed this arrangement in my sections. This is the most important Appendix. It has less of the nature of commentary than the previous four wings. While explaining much of what is found in the Text, it diverges to the origin of the trigrams, the methods pursued in the practice of divination, the rise of many arts in the progress of civilisation, and other subjects.

My fourth Appendix, also in two sections, forms the seventh 'wing.' It is confined to an amplification of the expositions of the first and second hexagrams by king Wăn and his son, purporting to show how they may be interpreted of man's nature and doings.

My fifth Appendix is the eighth 'wing,' called 'Discourses on the Trigrams.' It treats of the different arrangement of these in respect of the seasons of the year and the cardinal points by Fû-hsî and king Wăn. It contains also one paragraph, which might seem to justify the view that there is a mythology in the Yî.

My sixth Appendix, in two sections, is the ninth 'wing,'— (p. 28) 'a Treatise on the Sequence of the Hexagrams,' intended to trace the connexion of meaning between them in the order in which they follow one another in the Text of king Wăn.

My seventh Appendix is the tenth 'wing,' an exhibition of the meaning of the 64 hexagrams, not taken in succession, but promiscuously and at random, as they approximate to or are opposed to one another in meaning.

The authorship of the Appendixes

3. Such are the Appendixes of the Yî King. We have to enquire next who wrote them, and especially whether it be possible to accept the dictum that they were all written by Confucius. If they have come down to us, bearing unmistakeably the stamp of the mind and pencil of the great sage, we cannot but receive them with deference, not to say with reverence. If, on the contrary, it shall appear that with great part of them he had nothing to do, and that it is not certain that any part of them is from him, we shall feel entirely at liberty to exercise our own judgment on their contents, and weigh them in the balances of our reason.

There is no superscription of Confucius on any of the Appendixes

None of the Appendixes, it is to be observed, bear the superscription of Confucius. There is not a single sentence in any one of them ascribing it to him. I gave in the first chapter, on p. 2, the earliest testimony that these treatises were produced by him. It is that of Sze-mâ Khien, whose 'Historical Records' must have appeared about the year 100 before our era. He ascribes all the Appendixes, except the last two of them, which he does not mention at all, expressly to Confucius; and this, no doubt, was the common belief in the fourth century after the sage's death.

The third and fourth Appendixes evidently not from Confucius

But when we look for ourselves into the third and fourth Appendixes—the fifth, sixth, and seventh 'wings'—both of which are specified by Khien, we find it impossible to receive his statement about them. What is remarkable in both parts of the third is, the frequent occurrence of the formula, 'The Master said,' familiar to all readers of the Confucian Analects. Of course, the (p. 29) sentence following that formula, or the paragraph covered by it, was, in the judgment of the writer, in the language of Confucius; but what shall we say of the portions preceding and following? If he were the author of them, he would not thus be distinguishing himself from himself. The formula occurs in the third Appendix at least twenty-three times. Where we first meet with it, Kû Hsî has a note to the effect that 'the Appendixes having been all made by Confucius, he ought not to be himself introducing the formula, "The Master said;" and that it may be presumed, wherever it occurs, that it is a subsequent addition to the Master's text.' One instance will show the futility of this attempt to solve the difficulty. The tenth chapter of Section i commences with the 59th paragraph:—

'In the Yî there are four things characteristic of the way of the sages. We should set the highest value on its explanations, to guide us in speaking; on its changes, for the initiation of our movements; on its emblematic figures, for definite action, as in the construction of implements; and on its prognostications, for our practice of divination.'

This is followed by seven paragraphs expanding its statements, and we come to the last one of the chapter which says,—'The Master said, "Such is the import of the statement that there are four things in the Yî, characteristic of the way of the sages."' I cannot understand how it could be more fully conveyed to us that the compiler or compilers of this Appendix were distinct from the Master whose words they quoted, as it suited them, to confirm or illustrate their views.

In the fourth Appendix, again, we find a similar occurrence of the formula of quotation. It is much shorter than the third, and the phrase, 'The Master said,' does not come before us so frequently; but in the thirty-six paragraphs that compose the first section we meet with it six times.

Bearing of the conclusion as to the third and fourth on the other Appendixes

Moreover, the first three paragraphs of this Appendix are older than its compilation, which could not have taken place till after the death of Confucius, seeing it professes to quote his words. They are taken in fact from a narrative of the Žo Kwan, as having been spoken by a marchioness-dowager (p. 30) of Lû fourteen years before Confucius was born. To account for this is a difficult task for the orthodox critics among the Chinese literati. Kû Hsî attempts to perform it in this way:—that anciently there was the explanation given in these paragraphs of the four adjectives employed by king Wăn to give the significance of the first hexagram; that it was employed by Mû Kiang of Lû; and that Confucius also availed himself of it, while the chronicler used, as be does below, the phraseology of 'The Master said,' to distinguish the real words of the sage from such ancient sayings. But who was 'the chronicler?' No one can tell. The legitimate conclusion from KO's criticism is, that so much of the Appendix as is preceded by 'The Master said' is from Confucius,—so much and no more. I am thus obliged to come to the conclusion that Confucius had nothing to do with the composition of these two Appendixes, and that they were not put together till after his death. I have no pleasure in differing from the all but unanimous opinion of Chinese critics and commentators. What is called 'the destructive criticism' has no attractions for me; but when an opinion depends on the argument adduced to support it, and that argument turns out to be of no weight, you can no longer set your seal to this, that the opinion is true. This is the position in which an examination of the internal evidence as to the authorship of the third and fourth Appendixes has placed me. Confucius could not be their author. This conclusion weakens the confidence which we have been accustomed to place in the view that 'the ten wings' were to be ascribed to him unhesitatingly. The view has broken down in the case of three of them;—possibly there is no sound reason for holding the Confucian origin of the other seven.

I cannot henceforth maintain that origin save with bated breath. This, however, can be said for the first two Appendixes in my arrangement, that there is no evidence against their being Confucian like the fatal formula, 'The Master said.' So it is with a good part of my fifth Appendix; but the concluding paragraphs of it, as well as the seventh (p. 31) Appendix, and the sixth also in a less degree, seem too trivial to be the production of the great man. As a translator of every sentence both in the Text and the Appendixes, I confess my sympathy with P. Regis, when he condenses the fifth Appendix into small space, holding that the 8th and following paragraphs are not worthy to be translated. 'They contain,' he says, 'nothing but the mere enumeration of things, some of which may be called Yang, and others Yin, without any other cause for so thinking being given. Such a method of procedure would be unbecoming any philosopher, and it cannot be denied to be unworthy of Confucius, the chief of philosophers 30.'

I could not characterise Confucius as 'the chief of philosophers,' though he was a great moral philosopher, and has been since he went out and in among his disciples, the best teacher of the Chinese nation. But from the first time my attention was directed to the Yî, I regretted that he had stooped to write the parts of the Appendixes now under remark. It is a relief not to be obliged to receive them as his. Even the better treatises have no other claim to that character besides the voice of tradition, first heard nearly 400 years after his death.

The first Appendix

4. I return to the Appendixes, and will endeavour to give a brief, but sufficient, account of their contents.

The first bears in Chinese the name of Thwan Kwan, 'Treatise on the Thwan,' thwan being the name given to the paragraphs in which Wăn expresses his sense of the significance of the hexagrams. He does not tell us why he attaches to each hexagram such and such a meaning, nor why he predicates good fortune or bad fortune in connexion with it, for he speaks oracularly, after the manner of a diviner. It is the object of the writer of this Appendix to show the processes of king Wăn's thoughts in these operations, how he looked at the component trigrams with their symbolic intimations, their attributes and qualities, and their linear composition, till he could not think otherwise of the figures than he did. All these considerations are sometimes taken into account, (p. 32) and sometimes even one of them is deemed sufficient. In this way some technical characters appear which are not found in the Text. The lines, for instance, and even whole trigrams are distinguished as kang and zâu, hard or strong' and 'weak or soft.' The phrase Kwei-shăn, 'spirits,' or 'spiritual beings,' occurs, but has not its physical signification of 'the contracting and expanding energies or operations of nature.' The names Yin and Yang, mentioned above on pp. 15, 16, do not present themselves.

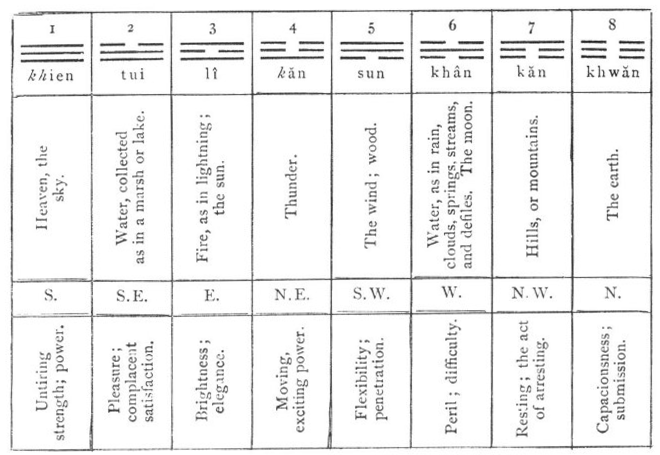

I delineated, on p. 11, the eight trigrams of Fû-hsî, and gave their names., with the natural objects they are said to represent, but did. not mention the attributes, the virtutes, ascribed to them. Let me submit here a table of them, with those qualities, and the points of the compass to which they are referred. I must do this because king Wăn made a change in the geographical arrangement of them, to which reference is made perhaps in his text and certainly in this treatise. He also is said to have formed an entirely different theory as to the things represented by the trigrams, which it will be well to give now, though it belongs properly to the fifth Appendix.

FÛ-HSÎ'S TRIGRAMS

(p. 33)

(p. 33)

The natural objects and phenomena thus represented are found up and down in the Appendixes. It is impossible to believe that the several objects were assigned to the several figures on any principles of science, for there is no indication of science in the matter: it is difficult even to suppose that they were assigned on any comprehensive scheme of thought. Why are tui and khân used to represent water in different conditions, while khân, moreover, represents the moon? How is sun set apart to represent things so different as wind and wood? At a very early time the Chinese spoke of 'the five elements,' meaning water, fire, wood, metal, and earth; but the trigrams were not made to indicate them, and it is the general opinion that there is no reference to them in the Yî"31.

Again, the attributes assigned to the trigrams are learned mainly from this Appendix and the fifth. We do not readily get familiar with them, nor easily accept them all. It is impossible for us to tell whether they were a part of the jargon of divination before king Wăn, or had grown up between his time and that of the author of the Appendixes.

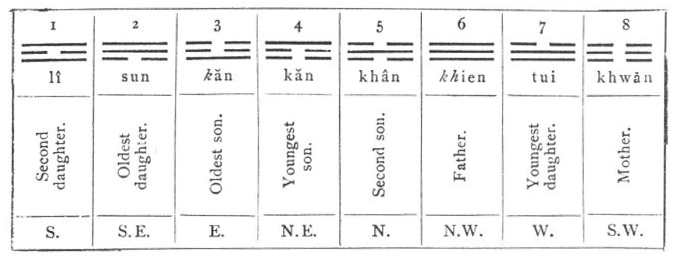

King Wăn altered the arrangement of the trigrams so that not one of them should stand at the same point of the compass as in the ancient plan. He made them also representative of certain relations among themselves, as if they composed a family of parents and children. It will be sufficient at present to give a table of his scheme.

KING WĂN'S TRIGRAMS

(p. 34)

(p. 34)

There is thus before us the apparatus with which the writer of the Appendix accomplishes his task. Let me select one of the shortest instances of his work. The fourteenth hexagram is , called Tâ Yû, and meaning 'Possessing in great abundance.' King Wăn saw in it the symbol of a government prosperous and realising all its proper objects; but all that he wrote on it was 'Tâ Yû (indicates) great progress and success.' Unfolding that view of its significance, the Appendix says:—

'In Tâ Yû the weak (line) has the place of honour, is grandly central, and (the strong lines) above and below respond to it. Hence comes its name of "Possession of what is great." The attributes (of its constituent trigrams, khien and lî) are strength and vigour, elegance and brightness. (The ruling line in it) responds to (the ruling line in the symbol of) heaven, and its actings are (consequently all) at the proper times. Thus it is that it is said to indicate great progress and success.'

In a similar way the paragraphs on all the other 63 hexagrams are gone through; and, for the most part, with success. The conviction grows upon the student that the writer has on the whole apprehended the mind of king Wăn.

The name Kwei-shăn

I stated, on p. 32, that the name kwei-shăn occurs in this Appendix. It has not yet, however, received the semi-physical, semi-metaphysical signification which the comparatively modern scholars of the Sung dynasty give to it. There are two passages where it is found;—the second paragraph on Khien, the fifteenth hexagram, and the third on Făng, the fifty-fifth. By consulting them the reader will be able to form an opinion for himself. The term kwei denotes specially the human spirit disembodied, and shăn is used for spirits whose seat is in heaven. I do not see my way to translate them, when used binomially together, otherwise than by spiritual beings or spiritual agents.

Kû Hsî once had the following question suggested by the second of these passages put to him:—'Kwei-shăn is a name for the traces of making and transformation; but when it is said that (the interaction of) heaven and earth (p. 35) is now vigorous and abundant, and now dull and void, growing and diminishing according to the seasons, that constitutes the traces of making and transformation; why should the writer further speak of the Kwei-shăn?' He replied, 'When he uses the style of "heaven and earth," he is speaking of the result generally; but in ascribing it to the Kwei-shăn, he is representing the traces of their effective interaction, as if there were men (that is, some personal agency) bringing it about"32.' This solution merely explains the language away. When we come to the fifth Appendix, we shall understand better the views of the period when these treatises were produced.

The single character shăn is used in explaining the thwan on Kwân, the twentieth hexagram, where we read:—

'In Kwân we see the spirit-like way of heaven, through which the four seasons proceed without error. The sages, in accordance with (this) spirit-like way, laid down their instructions, and all under heaven yield submission to them.'

The author of the Appendix delights to dwell on the changing phenomena taking place between heaven and earth, and which he attributes to their interaction; and he was penetrated evidently with a sense of the harmony between the natural and spiritual worlds. It is this sense, indeed, which vivifies both the thwan and the explanation of them.

The second Appendix

5. We proceed to the second Appendix, which professes to do for the duke of Kâu's symbolical exposition of the several lines what the Thwan Kwan does for the entire figures. The work here, however, is accomplished with less trouble and more briefly. The whole bears the name of Hsiang Kwan, 'Treatise on the Symbols' or 'Treatise on the Symbolism (of the Yî).' (p. 36) If there were reason to think that it came in any way from Confucius, I should fancy that I saw him sitting with a select class of his disciples around him. They read the duke's Text column after column, and the master drops now a word or two, and now a sentence or two, that illuminate the meaning. The disciples take notes on their tablets, or store his remarks in their memories, and by and by they write them out with the whole of the, Text or only so much of it as is necessary. Whoever was the original lecturer, the Appendix, I think, must have grown up in this way.

It would not be necessary to speak of it at greater length, if it were not that the six paragraphs on the symbols of the duke of Kâu are always preceded by one which is called 'the Great Symbolism,' and treats of the trigrams composing the hexagram, how they go together to form the six-lined figure, and how their blended meaning appears in the institutions and proceedings of the great men and kings of former days, and of the superior men of all time. The paragraph is for the most part, but by no means always, in harmony with the explanation of the hexagram by king Wăn, and a place in the Thwan Kwan would be more appropriate to it. I suppose that, because it always begins with the mention of the two symbolical trigrams, it is made, for the sake of the symmetry, to form a part of the treatise on the Symbolism of the Yî.

The Great Symbolism

I will give a few examples of the paragraphs of the Great Symbolism. The first hexagram is formed by a repetition of the trigram Khien representing heaven, and it is said on it:—'Heaven in its motion (gives) the idea of strength. The superior man, in accordance with this, nerves himself to ceaseless activity.'

The second hexagram is formed by a repetition of the trigram Khwăn representing the earth, and it is said on it:—'The capacious receptivity of the earth is what is denoted by Khwăn. The superior man, in accordance with this, with his large virtue, supports men and things.' (p. 37)

The forty-fourth hexagram, called Kâu is formed by the trigrams Sun , representing wind, and Khien representing heaven or the sky, and it is said on it:—'(The symbol of) wind, beneath that of the sky, forms Kâu. In accordance with this, the sovereign distributes his charges, and promulgates his announcements throughout the four quarters (of the kingdom).'

The fifty-ninth hexagram, called Hwân is formed by the trigrams Khân , representing water, and Sun , representing wind, and it is said on it:—(The symbol of) water and (that of wind) above it form Hwân. The ancient kings, in accordance with this, presented offerings to God, and established the ancestral temple.' The union of the two trigrams suggested to king Wăn the idea of dissipation in the alienation of men from the Supreme Power, and of the minds of parents from their children; a condition which the wisdom of the ancient kings saw could best be met by the influences of religion.

One more example. The twenty-sixth hexagram, called Tâ Khû , is formed of the trigrams Khien, representing heaven or the sky, and Kân , representing a mountain, and it is said on it:—'(The symbol of) heaven in the midst of a mountain forms Tâ Khû. The superior man, in accordance with this, stores largely in his memory the words of former men and their conduct, to subserve the accumulation of his virtue.' We are ready to exclaim and ask, 'Heaven, the sky, in the midst of a mountain! Can there be such a thing?' and Kû Hsî will tell us in reply, 'No, there cannot be such a thing in reality; but you can conceive it for the purpose of the symbolism.'

From this and the other examples adduced from the Great Symbolism, it is clear that, so far as its testimony bears on the subject, the trigrams of Fû-hsî did not receive their form and meaning with a deep intention that they should serve as the basis of a philosophical scheme concerning the constitution of heaven and earth and all that (p. 38) is in them. In this Appendix they are used popularly, just as one

'Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.'

The writer moralises from them in an edifying manner. There is ingenuity, and sometimes instruction also, in what he says, but there is no mystery. Chinese scholars and gentlemen, however, who have got some little acquaintance with western science, are fond of saying that all the truths of electricity, heat, light, and other branches of European physics, are in the eight trigrams. When asked how then they and their countrymen have been and are ignorant of those truths, they say that they have to learn them first from western books, and then, looking into the Yî, they see that they were all known to Confucius more than 2000, years ago. The vain assumption thus manifested is childish; and until the Chinese drop their hallucination about the Yî as containing all things that have ever been dreamt of in all philosophies, it will prove a stumbling-block to them, and keep them from entering on the true path of science.

The third Appendix

6. We go on to the third Appendix in two sections, being the fifth and sixth 'wings,' and forming what is called 'The Great Treatise.' It will appear singular to the reader, as it has always done to myself, that neither in the Text, nor in the first two Appendixes, does the character called Yî, which gives its name to the classic, once appear. It is the symbol of 'change,' and is formed from the character for 'the sun' placed over that for 'the moon"33.' As the sun gives place to the moon, and the moon to the sun, so is change always proceeding in the phenomena of nature and the experiences of society. We meet with the character nearly fifty times in this Appendix;—applied most commonly to the Text of our classic, so that Yî King or Yî Shû is 'the Classic or Book of Changes.' It is also applied often to the changes in the lines of the (p. 39) figures, made by the manipulations of divination, apart from any sentence or oracle concerning them delivered by king Wăn or his son. There is therefore the system of the Yî as well as the book of the Yî. The definition of the name which is given in one paragraph will suit them both:—'Production and reproduction is what is called (the process of) change"34.' In nature there is no vacuum. When anything is displaced, what displaces it takes the empty room. And in the lineal figures, the strong and the weak lines push each other out.

Harmony between the lines ever changing and the changes in external phenomena

Now the remarkable thing asserted is, that the changes in the lines of the figures and the changes of external phenomena show a wonderful harmony and concurrence. We read:—

'The Yî was made on a principle of accordance with heaven and earth, and shows us therefore, without rent or confusion, the course (of things) in heaven and earth"35.'

'There is a similarity between the sage and heaven and earth; and hence there is no contrariety in him to them. His knowledge embraces all things, and his course is intended to be helpful to all under the sky; and therefore he falls into no error. He acts according to the exigency of circumstances, without being carried away by their current; he rejoices in Heaven, and knows its ordinations; and hence he has no anxieties. He rests in his own (present) position, and cherishes the spirit of generous benevolence; and hence he can love (without reserve)"36.'

'(Through the Yî) he embraces, as in a mould or enclosure, the transformations of heaven and earth without any error; by an ever-varying adaptation he completes (the nature of) all things without exception; he penetrates to a knowledge of the course of day and night (and all other correlated phenomena). It is thus that his operation is spirit-like, unconditioned by place, while the changes (which he produces) are not restricted to any form.'

One more quotation:—

'The sage was able to survey all the complex phenomena under the sky. He then considered in his mind how they could be (p. 40) figured, and (by means of the diagrams) represented their material forms and their character"37.'

All that is thus predicated of the sage, or ancient sages, though the writer probably had Fû-hsî in his mind, is more than sufficiently extravagant, and reminds us of the language in 'the Doctrine of the Mean,' that 'the sage, able to assist the transforming and nourishing powers of heaven and earth, may with heaven and earth form a ternion"38.'

Divination

I quoted largely, in the second chapter, from this Appendix the accounts which it gives of the formation of the lineal figures. There is no occasion to return to that subject. Let us suppose the figures formed. They seem to have the significance, when looked at from certain points of view, which have been determined for us by king Wăn and the duke of Kâu. But this does not amount to divination. How can the lines be made to serve this purpose? The Appendix professes to tell us.

Ancient divination

Before touching on the method which it describes, let me observe that divination was practised in China from a very early time. I will not say 5,200 years ago, in the days of Fû-hsî, for I cannot repress doubts of his historical personality; but as soon as we tread the borders of something like credible history, we find it existing. In the Shû King, in a document that purports to be of the twenty-third century B. C."39, divination by means of the tortoise-shell is mentioned; and somewhat later we find that method continuing, and also divination by the lineal figures, manipulated by means of the stalks of a plant"40, the Ptarmica Sibirica"41, which is still cultivated on and about the grave of Confucius, where I have myself seen it growing.

Object of the divination

The object of the divination, it should be acknowledged, was not to discover future events absolutely, as if they could be known beforehand"42, but (p. 41) to ascertain whether certain schemes, and conditions of events contemplated by the consulter, would turn out luckily or unluckily. But for the actual practice the stalks of the plant were necessary; and I am almost afraid to write that this Appendix teaches that they were produced by Heaven of such a nature as to be fit for the purpose. 'Heaven,' it says, in the 73rd paragraph of Section i, quoted above on p. 14, 'Heaven produced the spirit-like things.' The things were the tortoise and the plant, and in paragraph 68, the same quality of being shăn, or 'spirit-like,' is ascribed to them. Occasionally, in the field of Chinese literature, we meet with doubts as to the efficacy of divination, and the folly of expecting any revelation of the character of the future from an old tortoise-shell and a handful of withered twigs"43; but when this Appendix was made, the writer had not attained to so much common sense. The stalks were to him 'spirit-like,' possessed of (p. 42) a subtle and invisible virtue that fitted them for use in divining.

Formation of the lineal figures by the divining stalks

Given the stalks with such virtue, the process of manipulating them so as to form the lineal figures is described (Section i, chap. 9, parr. 49-58), but it will take the student much time and thought to master the various operations. Forty-nine stalks were employed, which were thrice manipulated for each line, so that it took eighteen manipulations to form a hexagram. The lines were determined by means of the numbers derived from the River Map or scheme. Odd numbers gave strong or undivided lines, and even numbers gave the weak or divided. An important part was played in combining the lines, and forming the hexagrams by the four emblematic symbols, to which the numbers 9, 8, 7, 6 were appropriated"44. The figures having been formed, recourse was had for their interpretation to the thwan of king Wăn, and the emblematic sentences of the duke of Kâu. This was all the part which numbers played in the divination by the Yî, helping the operator to make up his lineal figure. An analogy has often been asserted between the numbers of the Yî and the numbers of Pythagoras; and certainly we might make ten, and more than ten, antinomies from these Appendixes in startling agreement with the ten principia of the Pythagoreans. But if Aristotle was correct in holding that Pythagoras regarded numbers as entities, and maintained that Number was the Beginning (Principle, ἀρχή) of things, the cause of their material existence, and of their (p. 43) modifications and different states, then the doctrine of the philosopher of Samos was different from that of the Yî"45, in which numbers come in only as aids in divining to form the hexagrams. Of course all divination is vain, nor is the method of the Yî less absurd than any other. The Chinese themselves have given it up in all circles above those of the professional quacks, and yet their scholars continue to maintain the unfathomable science and wisdom of these appended treatises!

The names Yin and Yang

It is in this Appendix that we first meet with the names yin and yang"46, of which I have spoken briefly on pp. p. 15, p. 16. Up to this point, instead of them, the names for the two elementary forms of the lines have been kang and zâu, which I have translated by 'strong and weak,' and which also occur here ten times. The following attempt to explain these different names appears in the fifth Appendix, paragraph 4:—

'Anciently when the sages made the Yî, it was with the design that its figures should be in conformity with the principles underlying the natures (of men and things), and the ordinances appointed (for them by Heaven). With this view they exhibited in them the way of heaven, calling (the lines) yin and yang; the way of earth, calling them the strong (or hard) and the weak (or soft); and the way of man, under the names of benevolence and righteousness. Each (trigram) embraced those three Powers, and being repeated, its full form consisted of six lines.'

However difficult it may be to make what is said here intelligible, it confirms what I have affirmed of the significance of the names yin and yang, as meaning bright and dark, derived from the properties of the sun and moon. We may use for these adjectives a variety of others, such as active and inactive, masculine and feminine, hot and cold, more or less analogous to them; but there arise the important questions,—Do we find yang and yin not merely used to indicate the quality of what they are applied (p. 44) to, but at the same time with substantival force, denoting what has the quality which the name denotes? Had the doctrine of a primary matter of an ethereal nature, now expanding and showing itself full of activity and power as yang, now contracting and becoming weak and inactive as yin:—had this doctrine become matter of speculation when this Appendix was written? The Chinese critics and commentators for the most part assume that it had. P. Regis, Dr. Medhurst, and other foreign Chinese scholars repeat their statements without question. I have sought in vain for proof of what is asserted. It took more than a thousand years after the closing of the Yî to fashion in the Confucian school the doctrine of a primary matter. We do not find it fully developed till the era of the Sung dynasty, and in our eleventh and twelfth centuries"47. To find it in the Yî is the logical, or rather illogical, error of putting 'the last first.' Neither creation nor cosmogony was before the mind of the author whose work I am analysing. His theme is the Yî,—the ever-changing phenomena of nature and experience. There is nothing but this in the 'Great Treatise' to task our powers;—nothing deeper or more abstruse. (p. 45)

The name Kwei-shăn

As in the first Appendix, so in this, the name kwei-shăn occurs twice; in paragraphs 21 and 50 of Section i. In the former instance, each part of the name has its significance. Kwei denotes the animal soul or nature, and Shăn, the intellectual soul, the union of which constitutes the living rational man. I have translated them, it will be seen, by 'the anima and the animus.' Canon McClatchie gives for them 'demons and gods;' and Dr. Medhurst said on the passage, 'The kwei-shăns are evidently the expanding and contracting principles of human life The kwei-shăns are brought about by the dissolution of the human frame, and consist of the expanding and ascending shăn, which rambles about in space, and of the contracted and shrivelled kwei, which reverts to earth and nonentity"48.'

This is pretty much the same view as my own, though I would not here use the phraseology of 'expanding and contracting.' Canon McClatchie is consistent with himself, and renders the characters by 'demons and gods.'

In the latter passage it is more difficult to determine the exact meaning. The writer says, that 'by the odd numbers assigned to heaven and the even numbers assigned to earth, the changes and transformations are effected, and the spirit-like agencies kept in movement;' meaning that by means of the numbers the spirit-like lines might be formed on a scale sufficient to give a picture of all the changing phenomena, taking place, as if by a spiritual agency, in nature. Medhurst contents himself on it with giving the explanation of Kû Hsî, that 'the kwei-shăns refer to the contractions and expandings, the recedings and approachings of the productive and completing powers of the even and odd numbers"49.' Canon McClatchie does not follow his translation of the former passage and give here 'demons and gods,' but we have 'the Demon-god (i.e. Shang Tî)"50.' I shall refer to this version when considering the fifth Appendix. (p. 46)

Shan alone

The single character shăn occurs more than twenty times;—used now as a substantive, now as an adjective, and again as a verb. I must refer the reader to the translation and notes for its various significance, subjoining in a note a list of the places where it occurs"51.

Much more might be said on the third Appendix, for the writer touches on many other topics, antiquarian and speculative, but a review of them would help us little in the study of the leading subject of the Yî. In passing on to the next treatise, I would only further say that the style of this and the author's manner of presenting his thoughts often remind the reader of 'the Doctrine of the Mean.' I am surprised that 'the Great Treatise' has never been ascribed to the author of that Doctrine, Žze-sze, the grandson of Confucius, whose death must have taken place between B. C. 400 and 450.

The fourth Appendix

7. The fourth Appendix, the seventh wing' of the Yî, need not detain us long. As I stated on p. 27, it is confined to an exposition of the Text on the first and second hexagrams, being an attempt to show that what is there affirmed of heaven and earth may also be applied to man, and that there is an essential agreement between the qualities ascribed to them, and the benevolence, righteousness, propriety, and wisdom, which are the four constituents of his moral and intellectual nature.

It is said by some of the critics that Confucius would have treated all the other hexagrams in a similar way, if his life had been prolonged, but we found special grounds for denying that Confucius had anything to do with the composition of this Appendix; and, moreover, I cannot think of any other figure that would have afforded to the author the same opportunity of discoursing about man. The style and method are after the manner of 'the Doctrine of the Mean' quite as much as those of 'the Great Treatise.' Several paragraphs, moreover, suggest to us the magniloquence of Mencius. It is said, for instance, by Žze-sze, of (p. 47) the sage, that 'he is the equal or correlate of Heaven"52,' and in this Appendix we have the sentiment expanded into the following:—

'The great man is he who is in harmony in his attributes with heaven and earth; in his brightness with the sun and moon; in his orderly procedure with the four seasons; and in his relation to what is fortunate and what is calamitous with the spiritual agents. He may precede Heaven, and Heaven will not act in opposition to him; he may follow Heaven, but will act only as Heaven at the time would do. If Heaven will not act in opposition to him, how much less will man! how much less will the spiritual agents"53!'

One other passage may receive our consideration:—

'The family that accumulates goodness is sure to have superabundant happiness, and the family that accumulates evil is sure to have superabundant misery"54.'

The language makes us think of the retribution of good and evil as taking place in the family, and not in the individual; the judgment is long deferred, but it is inflicted at last, lighting, however, not on the head or heads that most deserved it. Confucianism never falters in its affirmation of the difference between good and evil, and that each shall have its appropriate recompense; but it has little to say of the where and when and how that recompense will be given. The old classics are silent on the subject of any other retribution besides what takes place in time. About the era of Confucius the view took definite shape that, if the issues of good and evil, virtue and vice, did not take effect in the experience of the individual, they would certainly do so in that of his posterity. This is the prevailing doctrine among the Chinese at the present day; and one of the earliest expressions, perhaps the earliest expression, of it was in the sentence under our notice that has been copied from this Appendix into almost every moral treatise that circulates in China. A wholesome and an important truth it is, that 'the sins of parents are visited (p. 48) on their children;' but do the parents themselves escape the curse? It is to be regretted that this short treatise, the only 'wing' of the Yî professing to set forth its teachings concerning man as man, does not attempt any definite reply to this question. I leave it, merely observing that it has always struck me as the result of an after-thought, and a wish to give to man, as the last of 'the Three Powers,' a suitable place in connexion with the Yî. The doctrine of 'the Three Powers' is as much out of place in Confucianism as that of 'the Great Extreme.' The treatise contains several paragraphs interesting in themselves, but it adds nothing to our understanding of the Text, or even of the object of the appended treatises, when we try to look at them as a whole.

The fifth Appendix

8. It is very different with the fifth of the Appendixes, which is made up of 'Remarks on the Trigrams.' It is shorter than the fourth, consisting of only 22 paragraphs, in some of which the author rises to a height of thought reached nowhere else in these treatises, while several of the others are so silly and trivial, that it is difficult, not to say impossible, to believe that they are the production of the same man. We find in it the earlier and later arrangement of the trigrams,—the former, that of Fû-hsî, and the latter, that of king Wăn; their names and attributes; the work of God in nature, described as a progress through the trigrams; and finally a distinctive, but by no means exhaustive, list of the natural objects, symbolised by them.

First paragraph

It commences with the enigmatic declaration that 'Anciently, when the sages made the Yî,' (that is, the lineal figures, and the system of divination by them),'in order to give mysterious assistance .to the spiritual Intelligences, they produced (the rules for the use of) the divining plant.' Perhaps this means no more than that the lineal figures were made to 'hold the mirror up to nature,' so that men by the study of them would understand more of the unseen and spiritual operations, to which the phenomena around them were owing, than they could otherwise do. (p. 49)

The author goes on to speak of the Fû-hsî trigrams, and passes from them to those of king Wăn in paragraph 8. That and the following two are very remarkable; but before saying anything of them, I will go on to the 14th, which is the only passage that affords any ground for saying that there is a mythology in the Yî. It says:—

Mythology of the Yî

'Khien is (the symbol of) heaven, and hence is styled father. Khwăn is (the symbol of) earth, and hence is styled mother. Kăn (shows) the first application (of khwăn to khien), resulting in getting (the first of) its male (or undivided lines), and hence we call it the oldest son. Sun (shows) a first application (of khien to khwăn), resulting in getting (the first of) its female (or divided lines), and hence we call it the oldest daughter. Khân (shows) a second application (of khwăn to khien), and Lî a second (of khien to khwăn), resulting in the second son and second daughter. In Kăn and Tui we have a third application (of khwăn to khien and of khien to khwăn), resulting in the youngest son and youngest daughter.'

From this language has come the fable of a marriage between Khien and Khwăn, from which resulted the six other trigrams, considered as their three sons and three daughters; and it is not to be wondered at, if some men of active and ill-regulated imaginations should see Noah and his wife in those two primary trigrams, and in the others their three sons and the three sons' wives. Have we not in both cases an ogdoad? But I have looked in the paragraph in vain for the notion of a marriage-union between heaven and earth.

It does not treat of the genesis of the other six trigrams by the union of the two, but is a rude attempt to explain their forms when they were once existing"55. According to the idea of changes, Khien and Khwăn are continually varying their forms by their interaction. As here represented, the (p. 50) other trigrams are not 'produced"56' by a marriage-union, but from the application, literally the seeking, of one of them of Khwăn as much as of Khien—addressed to the other"57.

This way of speaking of the trigrams, moreover, as father and mother, sons and daughters, is not so old as Fû-hsî; nor have we any real proof that it originated with king Wăn. It is not of 'the highest antiquity.' It arose some time in 'middle antiquity,' and was known in the era of the Appendixes; but it had not prevailed then, nor has it prevailed since, to discredit and supersede the older nomenclature. We are startled when we come on it in the place which it occupies. And there it stands alone. It is not entitled to more attention than the two paragraphs that precede it, or the eight that follow it, none of which were thought by P. Regis worthy to be translated. I have just said that it stands 'alone.' Its existence, however, seems to me to be supposed in the fourth chapter, paragraphs 28-30, of the third Appendix, Section ii; but there only the trigrams of 'the six children' are mentioned, and nothing is said of 'the parents.' Kăn, khân, and kăn are referred to as being yang, and sun, lî, and tui as being yin. What is said about them is trifling and fanciful.

Operation of God in nature throughout the year

Leaving the question of the mythology of the Yî, of which I am myself unable to discover a trace, I now call attention to paragraphs 8-10, where the author speaks of the work of God in nature in all the year as a progress through the trigrams, and as being effected by His Spirit. The description assumes the peculiar arrangement of the trigrams, ascribed to king Win, and which I have exhibited above, on page 33"58. Father Regis adopts the general view (p. 51) of Chinese critics that Win purposely altered the earlier and established arrangement, as a symbol of the disorganisation and disorder into which the kingdom had fallen"59. But it is hard to say why a man did something more than 3000 years ago, when he has not himself said anything about it. So far as we can judge from this Appendix, the author thought that king Win altered the existing order and position of the trigrams with regard to the cardinal points, simply for the occasion,—that he might set forth vividly his ideas about the springing, growth, and maturity in the vegetable kingdom from the labours of spring to the cessation from toil in winter. The marvel is that in doing this he brings God upon the scene, and makes Him in the various processes of nature the 'all and in all.'

The 8th paragraph says:—

'God comes forth in Kăn (to his producing work); He brings (His processes) into full and equal action in Sun; they are manifested to one another in Lî; the greatest service is done for Him in Khwăn; He rejoices in Tui; He struggles in Khien; He is comforted and enters into rest in Khân; and he completes (the work of) the year in Kăn.'

God is here named Tî, for which P. Regis gives the Latin 'Supremus Imperator,' and Canon McClatchie, after him, 'the Supreme Emperor.' I contend that 'God' is really the correct translation in English of Tî; but to render it here by 'Emperor' would not affect the meaning of the paragraph. Kû Hsî says that 'by Tî is intended the Lord and Governor of heaven;' and Khung Ying-tâ, about five centuries earlier than Kû, quotes Wang Pî, who died A.D. (p. 52) 249, to the effect that 'Tî is the lord who produces (all) things, the author of prosperity and increase.'

I must refer the reader to the translation in the body of the volume for the 9th paragraph, which is too long to be introduced here. As the 8th speaks directly of God, the 9th, we are told, 'speaks of all things following Him, from spring to winter, from the east to the north, in His progress throughout the year.' In words strikingly like those of the apostle Paul, when writing his Epistle to the Romans, Wan Khung-žung (of the Khang-hsî period) and his son, in their admirable work called, 'A New Digest of Collected Explanations of the Yî King,' say:—'God (Himself) cannot be seen; we see Him in the things (which He produces).' The first time I read these paragraphs with some understanding, I thought of Thomson's Hymn on the Seasons, and I have thought of it in connexion with them a hundred times since. Our English poet wrote:—

'These, as they change, Almighty Father, these

Are but the varied God. The rolling year

Is full of Thee. Forth in the pleasing spring

Thy beauty walks, Thy tenderness and love.

Then comes Thy glory in the summer months,

With light and heat refulgent. Then Thy sun

Shoots full perfection through the swelling year.

Thy bounty shines in autumn unconfined,

And spreads a common feast for all that lives.

In winter awful Thou!'

Prudish readers have found fault with some of Thomson's expressions, as if they savoured of pantheism. The language of the Chinese writer is not open to the same captious objection. Without poetic ornament, or swelling phrase of any kind, he gives emphatic testimony to God as renewing the face of the earth in spring, and not resting till He has crowned the year with His goodness.

Concluding paragraphs

And there is in the passage another thing equally wonderful. The 10th paragraph commences:—'When we speak of Spirit, we mean the subtle presence (and operation of God) with all things;' and the writer goes on to illustrate this sentiment from the action and influences symbolised (p. 53) by the six 'children,' or minor trigrams,—water and fire, thunder and wind, mountains and collections of water. Kû Hsî says, that there is that in the paragraph which he does not understand. Some Chinese scholars, however, have not been far from descrying the light that is in it. Let Liang Yin, of our fourteenth century, be adduced as an example of them. He says:—'The spirit here simply means God. God is the personality (literally, the body or substantiality) of the Spirit; the Spirit is God in operation. He who is lord over and rules all things is God; the subtle presence and operation of God with all things is by His Spirit.' The language is in fine accord with the definition of shăn or spirit, given in the 3rd Appendix, Section i, 32.

I wish that the Treatise on the Trigrams had ended with the 10th paragraph. The writer had gradually risen to a noble elevation of thought from which he plunges into a slough of nonsensical remarks which it would be difficult elsewhere to parallel. I have referred on p. 31 to the judgment of P. Regis about them. He could not receive them as from Confucius, and did not take the trouble to translate them, and transfer them to his own pages, My plan required me to translate everything published in China as a part of the Yî King; but I have given my reasons for doubting whether any portion of these Appendixes be really from Confucius. There is nothing that could better justify the supercilious disregard with which the classical literature of China is frequently treated than to insist on the concluding portion of this treatise as being from the pencil of its greatest sage. I have dwelt at some length on the 14th paragraph, because of its mythological semblance; but among the eight paragraphs that follow it, it would be difficult to award the palm for silliness. They are descriptive of the eight trigrams, and each one enumerates a dozen or more objects of which its subject is symbolical. The writer must have been fond of and familiar with horses. Khien, the symbol properly of heaven, suggests to him the idea of a good horse; an old horse; a lean horse; and a piebald. Kăn, the symbol of thunder, suggests the (p. 54) idea of a good neigher; of the horse with white hind-legs; of the prancing horse; and of one with a white star in his forehead. Khân, the symbol of water, suggests the idea of the horse with an elegant spine; of one with a high spirit; of one with a drooping head; and of one with a shambling step. The reader will think he has had enough of these symbolisings of the trigrams. I cannot believe that the earlier portions and this concluding portion of the treatise were by the same author. If there were any evidence that paragraphs 8 to 10 were by Confucius, I should say that they were worthy, even more than worthy, of him; what follows is mere drivel. Horace's picture faintly pourtrays the inconsistency between the parts:—

'Desinit in piscem mulier formosa superne.'

In reviewing the second of these Appendixes, I was led to speak of the original significance of the trigrams, in opposition to the views of some Chinese who pretend that they can find in them the physical truths discovered by the researches of western science. May I not say now, after viewing the phase of them presented in these paragraphs, that they were devised simply as aids to divination, and partook of the unreasonableness and uncertainty belonging to that?

The sixth Appendix

9. The sixth Appendix is the Treatise on the Sequence of the Hexagrams, to which allusion has been made more than once. It is not necessary to dwell on it at length. King Wăn, it has been seen, gave a name to each hexagram, expressive of the idea—some moral, social, or political truth—which he wished to set forth by means of it; and this name enters very closely into its interpretation. The author of this treatise endeavours to explain the meaning of the name, and also the sequence of the figures, or how it is that the idea of the one leads on to that of the next. Yet the reader must not expect to find in the 64 a chain 'of linked sweetness long drawn out.' The connexion between any two is generally sufficiently close; but on the whole the essays, which I have said they form, resemble 'a heap of orient pearls at random strung.' The changeableness of human (p. 55) affairs is a topic never long absent from the writer's mind. He is firmly persuaded that 'the fashion of the world passeth away.' Union is sure to give place to separation, and by and by that separation will issue in re-union.

There is nothing in the treatise to suggest anything about its authorship; and as the reader will see from the notes, we are perplexed occasionally by meanings given to the names that differ from the meanings in the Text.

The seventh Appendix

10. The last and least Appendix is the seventh, called Žâ Kwâ Kwan, or 'Treatise on the Lineal Figures taken promiscuously,'—not with regard to any sequence, but as they approximate, or are opposed, to one another in meaning. It is in rhyme, moreover, and this, as much as the meaning, determined, no doubt, the grouping of the hexagrams. The student will learn nothing of value from it; it is more a 'jeu d'esprit' than anything else.

Footnotes

back 30 Regis' Y-King, vol. ii, p 576.

back 31 See Kâo Yî's Hâi Yü Žhung Khâo, Book I, art. 3 (1790).

back 32 See the 'Collected Comments' on hexagram 55 in the Khang-hsî edition of the Yî (App. I). 'The traces of making and transformation' mean the ever changing phenomena of growth and decay. Our phrase 'Vestiges of Creation' might be used to translate the Chinese characters. See the remarks of the late Dr. Medhurst on the hexagrams 15 and 55 in his 'Dissertation on the Theology of the Chinese,' pp. 107-112. In hexagram 15, Canon McClatchie for kwei-shăn gives gods and demons;' in hexagram 55, the Demon-gods.'

back 33

易 = 日, the sun, placed over 勿, a form of the old

(= 月), the moon.

(= 月), the moon.

back 34 III, i, 29 (chap. 5. 6).

back 35 III, i, 20 (chap. 4. 1).

back 36 III, i, 22.

back 37 III, i, 38 (chap. 8. 1).

back 38 Doctrine of the Mean, chap. xxii.

back 39 The Shû II, ii, 18.

back 40 The Shû V, iv, 20, 31.

back 41 See Williams' Syllabic Dictionary on the character 蓍 (Ptarmica Sibirica, Achillea sibirica).

back 42 Canon McClatchie (first paragraph of his Introduction) says:—'The Yî is regarded by the Chinese with peculiar veneration . . . . as containing a mine of p. 41 knowledge, which, if it were possible to fathom it thoroughly, would, in their estimation, enable the fortunate possessor to foretell all future events.' This misstatement does not surprise me so much as that Morrison, generally accurate on such points, should say (Dictionary, Part II, i, p. 1020, on the character 易):—

'Of the odd and even numbers, the kwâ or lines of Fû-hsî are the visible signs; and it being assumed that these signs answer to the things signified, and from a knowledge of all the various combinations of numbers, a knowledge of all possible occurrences in nature may be previously known.' The whole article from which I take this sentence is inaccurately written. The language of the Appendix on the knowledge of the future given by the use of the Yî is often incautious, and a cursory reader may be misled; to a careful student, however, the meaning is plain. The second passage of the Shû, referred to above, treats of 'the Examination of Doubts,' and concludes thus:—'When the tortoise-shell and the stalks are both opposed to the views of men, there will be good fortune in stillness, and active operations will be unlucky.'

back 43 A remarkable instance is given by Lîu Kî (of the Ming dynasty, in the fifteenth century) in a story about Shâo Phing, who had been marquis of Tung-ling in the time of Žhin, but was degraded tinder Han. Having gone once to Sze-mâ Ki-kû, one of the most skilful diviners of the country, and wishing to know whether there would be a brighter future for him, Sze-mâ said, 'Ah! is it the way of Heaven to love any (partially)? Heaven loves only the virtuous. What intelligence is possessed by spirits? They are intelligent (only) by their connexion with men. The divining stalks are so much withered grass; the tortoise-shell is a withered bone. They are but things, and man is more intelligent than things. Why not listen to yourself instead of seeking (to learn) from things?' The whole piece is in many of the collections of Kû Wăn, or Elegant Writing.

back 44 These numbers are commonly

derived from the River Scheme, in the outer sides of which are the corresponding

marks:—

, opposite to

, opposite to

;

;

,opposite to

,opposite to

;

;

opposite to

opposite to

; and

; and

, opposite to

, opposite to

. Hence the number 6 is assigned to

, 7 to

, 8 to

, and 9 to

.

Hence also, in connexion with the formation of the

figures by manipulation of the stalks, 9 becomes the number symbolical of the

undivided line, as representing Khien

and 6 of the divided line, as representing Khwăn

But the late delineation of the map, as given on

p. 15, renders all this uncertain, so far

as the scheme is concerned. The numbers of the hsiang, however, may have been

fixed, must have been fixed indeed, at an early period.

. Hence the number 6 is assigned to

, 7 to

, 8 to

, and 9 to

.

Hence also, in connexion with the formation of the

figures by manipulation of the stalks, 9 becomes the number symbolical of the

undivided line, as representing Khien

and 6 of the divided line, as representing Khwăn

But the late delineation of the map, as given on

p. 15, renders all this uncertain, so far

as the scheme is concerned. The numbers of the hsiang, however, may have been

fixed, must have been fixed indeed, at an early period.

back 45 See the account of Pythagoras and his philosophy in Lewes' History of Philosophy, pp. 18-38 (1871).

back 46 See Section i, 24, 32, 35; Section ii, 28, 29, 30, 35.

back 47 As a specimen of what the ablest Sung scholars teach, I may give the remarks (from the I Collected Comments') of Kû Kăn (of the same century as Kû Hsî, rather earlier) on the 4th paragraph of Appendix V:—In the Yî there is the Great Extreme. When we speak of the yin and yang, we mean the air (or ether) collected in the Great Void. When we speak of the Hard and Soft, we mean that ether collected, and formed into substance. Benevolence and righteousness have their origin in the great void, are seen in the ether substantiated, and move under the influence of conscious intelligence. Looking at the one origin of all things we speak of their nature; looking at the endowments given to them, we speak of the ordinations appointed (for them). Looking at them as (divided into) heaven, earth, and men, we speak of their principle. The three are one and the same. The sages wishing that (their figures) should be in conformity with the principles underlying the natures (of men and things) and the ordinances appointed (for them), called them (now) yin and yang, (now) the hard and the soft, (now) benevolence and righteousness, in order thereby to exhibit the ways of heaven, earth, and men; it is a view of them as related together. The trigrams of the Yî contain the three Powers; and when they are doubled into hexagrams, there the three Powers unite and are one. But there are the changes and movements of their (several) ways, and therefore there are separate places for the yin and yang, and reciprocal uses of the hard and the soft.'

back 48 Dissertation on the Theology of the Chinese, pp. 111, 112.

back 49 Theology of the Chinese, p. 122.

back 50 Translation of the Yî King, p. 312.

back 51 Section i, 23, 32, 51, 58, 62, 64, 67, 68, 69, 73, 76, 81; Section ii, 11, 15, 33, 34, 41, 45.

back 52 Kung-yung xxxi, 4.

back 53 Section i, 34. This is the only paragraph where kwei-shăn occurs.

back 54 Section ii, 5.

back 55 This view seems to be in accordance with that of Wû Khăng (of the Yüan dynasty), as given in the 'Collected Comments' of the Khang-hsî edition. The editors express their approval of it in preference to the interpretation of Kû Hsî, who understood the whole to refer to the formation of the lineal figures, the 'application' being 'the manipulation of the stalks to find the proper line.'

back 56 But the Chinese term Shăng 生, often rendered 'produced,' must not be pressed, so as to determine the method of production, or the way in which one thing comes from another.

back 57 The significance of the mythological paragraph is altogether lost in Canon McClatchie's version:—'Khien is Heaven, and hence he is called Father; Khwăn is Earth, and hence she is called Mother; Kăn is the first male, and hence he is called the eldest son,' &c. &c.

back 58 The reader will understand the difference in the two arrangements better by a reference to the circular representations of them on Plate III.

back 59 E. g. 1, 23, 24:—'Observant etiam philosophi (lib. 15 Sinicae philosophiae Sing-11) principem. Wăn-wang antiquum octo symbolorum, unde aliae figurae omnes pendent, ordinem invertisse; quo ipsa imperii suis temporibus subversio graphice exprimi poterat, mutatis e naturali loco, quem genesis dederat, iis quatuor figuris, quae rerum naturalium pugnis ac dissociationibus, quas posterior labentis anni pars afferre solet, velut in antecessum, repraesentandis idoneae videbantur; v. g. si symbolum Lî, ignis, supponatur loco symboli Khân, aquae, utriusque elementi inordinatio principi visa est non minus apta ad significandas ruinas et clades reipublicae male ordinatae, quam naturales ab hieme aut imminente aut saeviente rerum generatarum corruptiones.' See also pp. 67, 68.